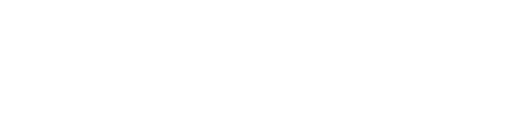

It’s a familiar scene.

The surgery went smoothly. The grafts are patent. Vitals are stable. But a day or two post-op, the family says, “He’s not himself.”

The patient—once sharp, articulate, and quick with words—now struggles to find them. Confused. Slower. Sometimes withdrawn.

That’s often called Pump Head Syndrome—a term that’s lingered in surgical corridors for decades but still lives in a grey zone of understanding. Clinically, we know it as postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) after cardiopulmonary bypass. It’s real, it’s measurable, and in some cases, it doesn’t fully resolve.

Yet despite its prevalence, it often slips through the cracks—misattributed to age, anesthesia, or just “normal recovery.”

This article takes a clear, clinical look at the cognitive consequences of bypass surgery—what causes them, who’s at risk, and what we can do about it. No fluff. No fear-mongering. Just what we know, and why it matters.

Why the Brain Gets Foggy After Heart Surgery

Heart surgery often uses something called a heart-lung machine. It keeps blood and oxygen moving through the body while the heart is stopped during surgery. This machine saves lives—but it’s not perfect. And sometimes, it leaves the brain feeling off afterward.

Here’s why that can happen—based on real research from top heart doctors and brain experts:

1- Tiny Particles Can Slip into the Brain

During surgery, microscopic bubbles or tiny bits of debris can get into the blood and travel to the brain. These are too small to cause a stroke—but they can still cause tiny “hits” to brain cells.

Doctors call these microemboli, and they’ve been seen in many studies during bypass surgery.

2- Blood Flow and Oxygen Might Dip

During surgery, blood pressure can drop, even for a short time. That means the brain might not get enough oxygen, especially in areas that are more sensitive.

The result? Trouble thinking clearly afterward—even if everything else went well.

3- Surgery Itself Is a Lot for the Brain

Long operations, deep sleep from anesthesia, and the stress of major surgery can leave the brain feeling tired and confused.

This is even more common in older adults, or people who already had some memory or thinking issues before surgery.

Prevent heart problems before they start – Schedule a preventive checkup

Contact UsHow Common Is Pump Head Syndrome?

It’s more common than most people think—and it’s often under-reported.

Here’s what research shows:

- Right after surgery, up to 50–60% of heart surgery patients show some level of thinking or memory problems.

These can include trouble focusing, forgetfulness, slow thinking, or just feeling “off.” - The good news?

For most people, the brain starts to clear up within a few weeks.

By 3 to 6 months, that number drops to about 10–20% who still feel lingering effects. - A smaller group—usually older adults or people with prior brain or memory issues—can have changes that last longer, sometimes over a year.

The risk goes up with:

- Older age (especially over 65)

- Long surgeries

- Previous strokes or memory issues

- Complicated procedures or repeat surgeries

Important to Know

Doctors used to think this was “just aging” or “normal recovery.”

But now, research has confirmed this is a real and measurable problem. It even has a medical name:

Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction or POCD—sometimes called “Pump Head” in everyday language.

How to Lower the Risk of Brain Fog After Heart Surgery

We can’t stop every case of cognitive issues after surgery—but there are real ways to reduce the risk. Doctors, hospitals, and even patients themselves can all play a part.

Here’s what helps:

1. Choosing the Right Surgical Team

This matters more than most people think.

Experienced heart surgeons and well-coordinated surgical teams know how to minimize time on the heart-lung machine, reduce blood pressure dips, and avoid complications that raise the risk of brain changes.

More precision in the OR = less stress on the brain.

2. Shorter Bypass Time

The longer a person is on the heart-lung machine, the greater the chance of small brain hits.

That’s why doctors now aim to keep bypass time as short as safely possible.

Less time on the machine, lower risk for the brain.

3. Better Blood Pressure and Oxygen Control

During surgery, keeping the brain well-perfused—meaning enough oxygen and blood flow—is key.

Modern anesthetic teams are trained to watch this closely and keep the brain protected during the whole operation.

4. Avoiding Low Blood Counts

If blood levels drop too low during or after surgery, it can affect brain oxygen.

That’s why many hospitals now aim for fewer transfusions and better blood management.

5. Treating Other Health Problems First

People with high blood pressure, diabetes, or irregular heartbeats (like AFib) are at higher risk.

Managing these before surgery helps protect the brain after.

6. Early Mobilization After Surgery

Once surgery is done, getting the patient up and moving (even just sitting up) helps the brain recover faster.

Lying in bed for days slows the brain down.

Movement wakes the body—and the brain.

7. Cognitive Training (Yes, Brain Exercises!)

Some hospitals now offer simple memory and thinking games before and after surgery.

This is a new area of research, but studies suggest it might help the brain stay sharper.

Can You Prevent It 100%?

Not always. But with the right care, the risk can be lowered a lot.

And if brain fog does happen, catching it early means you can support recovery right away.

Prevent heart problems before they start – Schedule a preventive checkup

Contact UsWords By Author

Pump Head Syndrome isn’t a myth. It’s real. It’s common. And it catches people off guard—not because the surgery went wrong, but because the brain is more sensitive than we realize.

The good news?

For most people, these changes are temporary. The fog lifts. The sharpness returns.

But knowing what to expect—and acting early if something feels off—can make all the difference.

So whether you’re a patient, a family member, or a clinician:

Watch the mind as closely as the heart.

Recovery doesn’t just happen in the chest. It happens in the head, too.